-

-

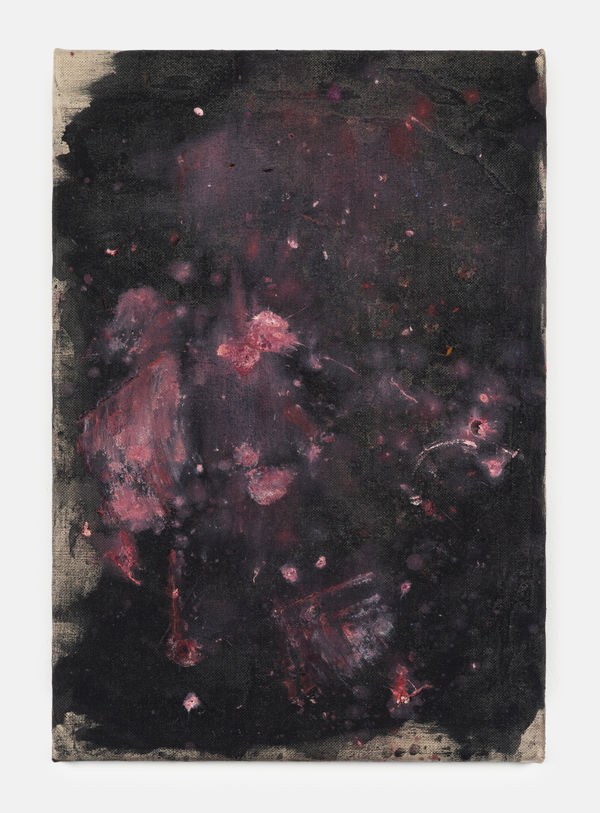

Galerie Peter Kilchmann is pleased to present Heavy Mental, the first solo exhibition of new paintings, sculptures and drawings by Berlin-based artist Tobias Spichtig (b. 1982, Lucerne, Switzerland). For Spichtig, painting is a way of staying sane or (doing insane things). Like Ozzy Osbourne howling into the void of teenage bedrooms, it’s almost a method—half-joke, half-truth—for not losing your mind while losing it.The exhibition title, Heavy Mental speaks to a tension at the heart of Spichtig’s work. What remains central in Spichtig’s work is not a fixed iconography but a sensibility shaped by the raw texture of adolescence, the intensity of which remains in subcultural experience, and the aesthetics of affect throughout life. Music is a structuring influence: not in a directly referential way, but as a conceptual and emotional device. Metal, in this formulation, becomes both symbol and tool— a language of extremity, a container for unruly feeling, a mode of living. Not a representation of the world, but a way of being inside it: a way of staying sane by joining “the circus of the dark.”Painting, in this light, becomes a similarly charged activity: a form of self-inscription performed on the edge of chaos. Heavy metal here becomes a metaphor, not just a genre. It stands for everything uncontainable in language— everything felt too much or too early. The fantasy of heavy metal—the drama, the distortion, the darkness —is also real, Spichtig insists. It holds the power of something both juvenile and profound, simultaneously ridiculous and sincere.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

For Spichtig, painting, like music, begins not with thinking, but with a pulse—something sensed or intuited before it becomes visible. The studio, like a music studio, is not a space of control but of vulnerability, for allowing something through. “First dreaming, then painting,” he says, “and maybe later thinking.” This reversal of logic—in which emotion precedes form, and form precedes interpretation—is central to the experience of his work. The point isn’t to understand the world, but to conjure a version of it where sensation comes before sense, where the painting is the future because it hasn’t fully arrived yet.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

The figures in Spichtig’s paintings appear drained, floating, spectral—somewhere between ghosts and idols. They carry the echo of music posters, burned-out social feeds, and teenage bedroom walls when everything felt both insane, deeply meaningful, mad and fun. His portraits don’t perform identity; they haunt it. The new works do not so much represent feelings as they emit them, steeped in the residue of moods we recognize but cannot easily name. They are less about narrative or interpretation than they are about the texture of a moment, a state of mind, a sound still reverberating long after it ends.This paradox—of feeling both too much and not enough—resonates in the paintings. The figures in Heavy Mental are both radically present and overwhelmingly charged. Their blank stares and emptied eyes do not nullify affect, but intensify it, the viewer becomes a screen onto which emotion is projected—melancholy, yearning, alienation, recognition.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Tobias SpichtigUntitled, 2025Oil on linen140 x 150 cm (55 ⅛ x 59 in.)In this haunting triad of skull-faced figures, Spichtig doesn’t paint death—he paints what it feels like to be alive inside a world that’s already burning. The three skeletal faces, emerging from a haze of black and bleeding crimson, don’t evoke horror so much as recognition. This isn’t memento mori, its a portrait not of mortality, but of affect—raw, blown-out, and wired through with noise.Here, painting becomes what it is for Spichtig at its core: a ritual of emotional invocation. The figures, staring blankly yet intimately out of the void, are neither caricatures nor narrative subjects. They don’t represent feeling—they transmit it. Like the icons on the wall of a teenager’s room, these skulls are both absurd and sacred. Their long, streaked hair and heavy shadows recall band members on an album cover, ghosted friends in selfies, or lovers once lit by a dim red lamp. Their affect is blank, yet the emotional charge is thick with melancholy and devotion.

Tobias SpichtigUntitled, 2025Oil on linen140 x 150 cm (55 ⅛ x 59 in.)In this haunting triad of skull-faced figures, Spichtig doesn’t paint death—he paints what it feels like to be alive inside a world that’s already burning. The three skeletal faces, emerging from a haze of black and bleeding crimson, don’t evoke horror so much as recognition. This isn’t memento mori, its a portrait not of mortality, but of affect—raw, blown-out, and wired through with noise.Here, painting becomes what it is for Spichtig at its core: a ritual of emotional invocation. The figures, staring blankly yet intimately out of the void, are neither caricatures nor narrative subjects. They don’t represent feeling—they transmit it. Like the icons on the wall of a teenager’s room, these skulls are both absurd and sacred. Their long, streaked hair and heavy shadows recall band members on an album cover, ghosted friends in selfies, or lovers once lit by a dim red lamp. Their affect is blank, yet the emotional charge is thick with melancholy and devotion. -

-

Despite the dark tonalities, Spichtig’s work resists cynicism. These paintings are neither nostalgic nor ironic, though they frequently mine the detritus of pop culture and youth memory. Instead, they suggest that the remnants of such images—recycled, half-remembered, emotionally charged—can offer a different kind of truth. Aesthetic decisions are not simply stylistic but existential: how to render feeling without spectacle, how to invoke depth in an image culture so defined by surface. His figures appear as if lit from within by a past that won’t go away, but also not entirely present either—a temporal dissonance that defines their haunting quality.

-

-

-

Spichtig’s practice is grounded in a persistent negotiation with presence, absence, and the conditions of perception. While his paintings are resolutely figurative, his portraits are as much intimate likenesses as idols—figures rendered with the stylized detachment of a magazine cover or bedroom poster, gesturing toward a collective escaping of feelings, fragmentation, and dislocation but pointing towards something to long for. In their hollowed gazes and affectless stillness, one senses a generation caught between visibility and dissolution, between the illusion of knowing and the reality of never quite arriving at meaning. What connects these figures is the gaze that shapes them, one that remains unchanged whether painting those closest to him—friends, collaborators—or long-admired cultural figures. Spichtig’s gaze remains constant: a fan’s awe, pure and unrelenting. In this Warholian perspective everyone is both person and myth. The artist’s admiration is not diminished by proximity—if anything, it deepens, becoming less about fantasy and more about shared history, presence and feelings.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

For his sculptures, Spichtig usually uses second-hand clothing, often from friends, which he immerses in resin and occasionally coats with nickel, or other metals. For the first time with Galerie Peter Kilchmann he produced his signature silhouettes in bronze, finished with a subtle greenish patina, by casting an original resin sculpture and burning it out. The result is a spindly, cloaked and elongated figure that stands in an up-straight-manner on a pair of swimming flippers, originally intended for diving. The very fabric details of the clothing items is distinctly visible in the bronze cast, leaving richly textured marks on the work and resembling the fabrication traces of sculptures of artists like Hans Josephson. The unusual pairing comes from a coincidence to try and stabilize the fragile and thinned out sculptures with elements found in his studio. Its draped, hooded form is frozen in folds—evoking both the ephemeral quality of a garment and its texture in motion and the stiffness of a wax figure or mannequin. These figure appear post-human, puppet-like, evoking an eerie stillness. Supported by the simple pose, the one of a random bystander, spectator or visitor, the form remains anonymous and void-like—typical of Spichtig’s figures that serve more as symbols of presence than actual individual.

-

-

If there’s a joke here, it’s surely not at the viewer’s expense. It’s about the absurdity and beauty of daily life. But also: the joke is sacred. Because it’s not just a joke. Heavy metal, teenage fantasy, crisis disguised as cool— and all great madness still works. Half a life later, the same sounds still sound great. The same images remain just as resonant. Spichtig’s paintings offer that same kind of unplaceable power: simultaneously out-of-time yet absolutely contemporary.

-

-

-

-

-

For further information, please contact inquiries@peterkilchmann.com

-

Galerie Peter Kilchmann

Zahnradstrasse 21, Zurich

, 13 June - 25 July 2025Be the first to know updates about Galerie Peter Kilchmann

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied to communicate with you in accordance with our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.